Dental practitioners may introduce various materials and objects into the upper respiratory and digestive tracts during treatment. Foreign bodies such as endodontic instruments, orthodontic bands, dental implants and their accessories, restorative materials, and rotating instruments may be swallowed or inhaled during the diagnostic and therapeutic process, posing potential risks.

Among these incidents, accidental ingestion is the most common, which can lead to serious health problems. However, although aspiration accounts for only about 13% of accidents, it seems to pose a greater danger.

Inhaled objects tend to preferentially enter the right main bronchus because it has a smaller angle with the trachea compared to the left main bronchus. Once a foreign body enters the lungs, it can cause complications including airway obstruction, pneumonia, and lung abscess. Bronchoscopy can be attempted to remove the foreign body, with reported success rates as high as 99%. Although in rare cases thoracotomy or surgical resection may be necessary, and in some instances even lobectomy may be required when the foreign body cannot be successfully retrieved.

However, swallowed materials pose a different type of risk. Generally, these objects can safely pass through the gastrointestinal tract and be expelled without further issues. However, sharp objects may cause intestinal perforation, leading to serious consequences such as peritonitis. This is especially important considering that the most commonly reported swallowed dental materials include dentures or crowns, rotating instruments, and root canal files and drills, all of which have jagged or sharp edges. Given the potential for pathogenicity and even, though less likely, mortality, dentists should be aware of the potential risks of these complications and take appropriate preventive measures to avoid these mostly avoidable situations.

This clinical report describes an incident of impression material retention in the patient’s hypopharynx during the impression process and provides guidance for the management and prevention of foreign body swallowing and aspiration.

Case Report

A 71-year-old male patient presented to the oral clinic at the University of Kentucky College of Dentistry. The purpose of the visit was to take final impressions for complete maxillary and mandibular dentures. His medical history included hypertension and a mild swallowing difficulty following a cerebrovascular accident 5 years prior. The patient’s vital signs on the day of the visit were within normal limits. The operator evaluated individual trays for the maxillary arch, adjusted the tray’s borders, created relief holes, and applied tray adhesive to the tray according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Polyvinyl siloxane impression material was placed in the tray. The operator placed the tray on the edentulous soft tissue of the maxillary arch and waited for the material to polymerize for 5 minutes.

When the tray was removed from the patient’s mouth, he felt slightly nauseous. The operator noticed a thin, thread-like, already polymerized impression material at the posterior part of the tray, which seemed to have separated or torn from another part of the impression material that was not seen. The patient coughed several times and stated that he felt something at the bottom of his throat but could not swallow or remove it. He was able to speak and swallow without signs of respiratory distress.

Subsequently, the patient was taken to the emergency department, and an otolaryngologist examined his throat, confirming the retention of the impression material in the hypopharynx. Emergency department staff made multiple attempts to assist the patient in expelling the foreign body, but were unsuccessful. The physician requested a lateral cervical X-ray (Figure 1). The radiologist reviewed the neck X-ray and reported no obvious radiographic findings. The otolaryngologist then decided to prepare the patient for the operating room to remove the foreign body effectively.

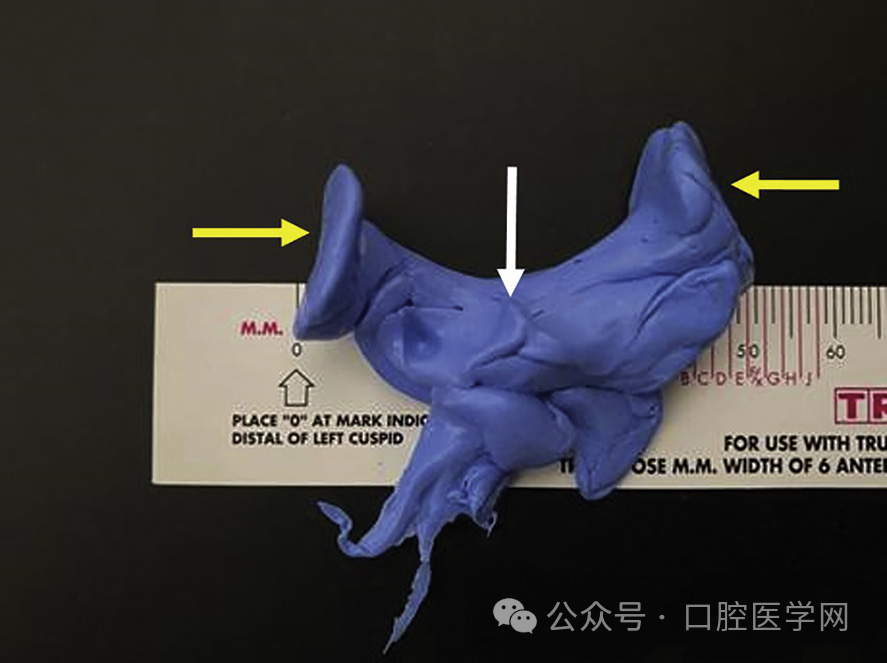

As he bent over to untie his shoelaces to prepare to enter the operating room, he coughed forcefully, expelling the foreign body as shown in Figure 2. The otolaryngologist examined the hypopharynx again, confirming the absence of the foreign body. An oral maxillofacial surgeon examined the expelled mass and confirmed its consistency with the impression material. The patient did not experience any further complications after this incident.

Based on the appearance of the expelled impression material, it appeared to be lodged in the posterior aspect of the hypopharynx. The material replicated several anatomical structures, including the valleculae and bilateral piriform fossae (Figure 2).

Discussion

This clinical report reveals an unusual case that highlights the various foreign objects that can be inhaled or swallowed during dental treatment. Given the morbidity and mortality that can result from such incidents, all dental practitioners must take preventive measures to reduce the occurrence of these events.

This patient had a history of cerebrovascular accident, which resulted in motor impairment and decreased gag reflex, making him susceptible to aspiration. Additionally, it has been reported that patients aged 60 to 79 are more prone to foreign body aspiration.

To prevent such events from recurring, several strategies were identified to reduce risks: avoid having patients lie down during impression procedures, use impression materials with appropriate viscosity for specific procedures, avoid overfilling impression trays, remove excess impression material that overflows from the posterior part of the tray with a mouth mirror, maintain focus and remain present with the patient during the impression process, and contact radiology staff familiar with the anatomy of the relevant area and capable of identifying abnormal radiodensities when an incident of foreign body ingestion or aspiration occurs.

If an object is found to be missing during a dental procedure, an appropriate management plan should be initiated immediately. At the moment of an incident, attempts can be made to remove it using suitable non-invasive suction devices such as a Yankauer suction tip or appropriate retrieval instruments like Magill forceps. Additionally, there have been reports of using magnets to extract swallowed metallic objects, particularly batteries.

If the object cannot be visualized directly, immediate arrangements should be made for appropriate imaging studies to locate the foreign body. The management of any lost foreign object during dental treatment will depend on its location, which needs to be determined through medical imaging, and therefore referral to an appropriate specialist for further management is recommended.

In case of aspiration, bronchoscopy may be recommended, and if bronchoscopy is unsuccessful, thoracotomy may need to be considered. If the object is swallowed, the patient may need to undergo continuous bowel movements to search for the foreign body. If the foreign body is not found after multiple bowel movements, additional imaging studies should be considered due to individual variation in gastrointestinal transit times. It has been reported that the maximum upper limit of colonic transit in non-constipated individuals is approximately 45.6 hours. When incidents of dental instrument aspiration or swallowing occur, it is necessary to seek medical consultation and professional guidance.

Impression materials pose a particular situation because most other swallowed or inhaled dental materials, due to the presence of metal components (such as crowns, root canal files), would present obvious high-density radiopaque appearances on radiographs. In this clinical report, the retained impression material did not exhibit a significant high-density radiographic appearance, and the initial radiologic interpretation failed to detect the material. In this case, the radiodensity of the material may have overlapped with calcifications in the hypopharyngeal structures shown in Figure 1, which complicated its radiographic detection. However, there are reports in the literature indicating that certain impression materials lack radiopacity, and radiologists should be aware of this information before interpreting images.

Polyvinyl siloxane impression materials have significant radiopacity due to the presence of lead dioxide, but experimental evidence shows that polyether silicone, polyether, and alginate impression materials have relatively higher radiolucency. In at least one reported case, the relative radiolucency of polyvinyl siloxane material was crucial clinically. The authors suggest that future standards for such impression materials should include requirements for enhanced radiopacity to better visualize such materials through medical imaging techniques. Similar recommendations have been made regarding other biomedical devices and dentures. Currently, some elastic impression materials with enhanced radiopacity and biocompatibility are being developed.

Cameron et al. reported a patient who had a 3-year history of “asthma” that was later discovered to be due to the inhalation of polyvinyl siloxane impression material. Interestingly, this patient was forced into early retirement due to the condition, and the diagnosis was only made after an otolaryngologist removed the material using a bronchoscope. The radiographic image did not show the PVS material, which was attributed to its lack of radiopacity. Similarly, Rodrigues et al. reported a patient with a long-standing history of sinusitis caused by impression material.

Conclusion

The inhalation or ingestion of foreign bodies is a recognized hazard in dental treatment. Although most reports mention that foreign bodies pass harmlessly through the digestive tract, they can have serious sequelae. Dental teams must use relevant strategies to reduce risks and identify and minimize risk factors as much as possible. Dentists must be knowledgeable about the management of these emergency situations in case they occur.

Leave a Reply