By: Professor Chen Yaming

In the field of dentistry, crown restoration is a common yet essential treatment modality. Today, let’

s discuss metal crowns, a significant component of crown restorations, and reflect on my memories related to this topic.

Metal crowns, colloquially known as metal caps, are employed when teeth are compromised due to various reasons such as caries or trauma. After initial treatment with restorative materials, a dentist fabricates a protective metal structure, akin to a cap, which is then bonded to the tooth using a dental adhesive, thus referred to as a metal crown.

Several types of metal materials are utilized in crown fabrication. Gold alloys were among the earliest materials used due to gold’s superior corrosion resistance and excellent malleability, allowing for a snug fit that remains aesthetically pleasing over time without degrading. However, due to the high cost of gold, more economical alternatives like nickel-chromium and cobalt-chromium alloys emerged. In terms of fabrication techniques, crowns could be produced using the stamping and forging method, which involves forming a preformed cap structure through a series of manual stamping and forging processes.

From 1989 to around 1996, I treated patients directly, performing tooth preparations and taking impressions, which were then brought back to the lab for subsequent processing. Another method involved the lost-wax casting technique, necessitating hands-on skill to create cast metal crowns for patients.

Mastering techniques such as forging, casting, wax pattern creation, investment, casting, operation of high-frequency centrifugal casting machines, tooth sculpting, bending retentive rings, polishing cast frameworks, artificial tooth arrangement, and boxing was essential. This process proved challenging for me as a recent graduate from Beijing working in Nanjing. However, through continued practice and learning, I quickly acquired these skills, laying a solid foundation for my later teaching in prosthodontics and for establishing a dental restoration technology program at my university over a decade later.

Due to my busy schedule in clinical prosthodontics and the fabrication of various prosthetic appliances, I sometimes felt less like a doctor. I vividly remember one afternoon when a relative from my hometown visited. I hastily paused my work in the lab to greet him. Upon seeing me, he expressed surprise, saying, “Back when you graduated, wearing a white coat in the ward and clinic, performing surgeries, you looked very much like a doctor. But now, after finishing your graduate studies in Beijing and working in Nanjing, you look like a workshop worker, even with gypsum powder on your shoes!” His comment made me chuckle.

As time passed and living standards improved, expectations for restorations also rose. Metal crowns, often aesthetically unpleasing and clashing with the color of natural teeth, were no longer the preferred option for anterior restorations.

To enhance appearance, dentists began to create a small window on the buccal or facial surface of metal crowns to reveal the tooth color. In prosthodontic terminology, this design is referred to as a “window crown.” Although this offered slight aesthetic improvement, the visible metal edges were still not ideal. Consequently, dentists started reducing tooth size and using the technique of bonding a layer of porcelain to a metal substructure, combining the strength of metal with the aesthetic qualities of porcelain. The resulting crowns closely resembled natural teeth, rapidly gaining popularity and becoming the preferred choice for crown restorations.

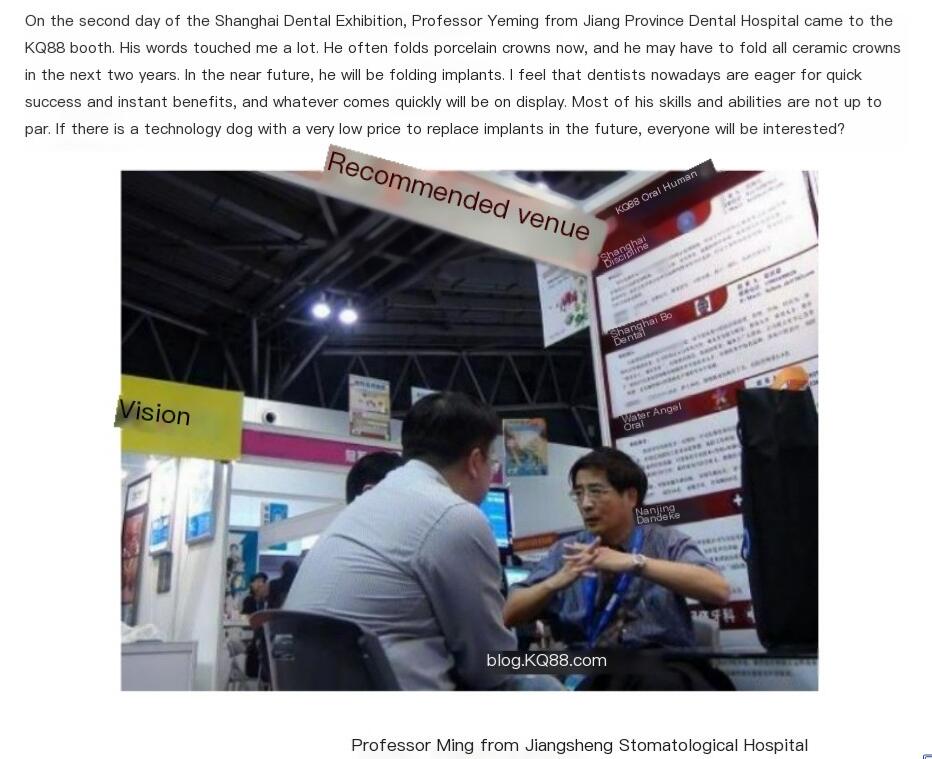

From the late 1980s to the late 1990s, porcelain-fused-to-metal crowns experienced a peak in usage. Due to their higher cost compared to metal crowns and their improved aesthetics, the dental industry saw a surge in their production driven by economic incentives and other factors. Many dentists, lacking mastery in restorative techniques, enthusiastically produced porcelain crowns for patients, creating significant concerns among my colleagues. I once vocally warned, “It won’t be long before we enter an era of removing porcelain crowns!”

A few years later, the adverse effects of improperly placed porcelain crowns became evident. By the mid-1990s, our clinical practice began to receive many patients requiring the removal of porcelain crowns.

Leave a Reply