Accidental Displacement of Oral Implants to the Maxillary Sinus: A Clinical Complication

Accidental displacement of dental implants into the maxillary sinus is a well-known clinical complication. However, migration of these implants into the ethmoidal sinus, sphenoidal sinus, nasal cavity, and anterior cranial fossa is exceedingly rare.

In certain cases, implant restoration in the posterior maxillary region can be particularly challenging due to unfavorable local conditions that might lead to implant displacement. These factors include excessive maxillary sinus pneumatization, insufficient bone volume, alveolar ridge resorption, poor bone quality, and undetected pathways between the maxillary sinus and the oral cavity.

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, there have been no reported cases of non-zygomatic dental implants migrating to the orbital cavity. This article aims to introduce and discuss a case involving the management of a dental implant displaced into the orbital cavity.

Case Report

A 40-year-old female patient was referred by her dentist to the Department of Maxillofacial Surgery at San Giovanni Battista Hospital, University of Turin, Italy. Two days prior, the patient underwent a dental implant procedure, involving the placement of three implants in the upper right molar region. During the surgery, one implant was reported to have migrated and was subsequently lost from the operator’s view.

The dental surgeon then expanded the oroantral fistula in an attempt to retrieve the implant using suction. During this process, the patient reported severe, sudden eye pain accompanied by flashing dark spots. Consequently, the surgery was halted, the intraoral surgical site was sutured, and the patient was referred to our department.

Upon examination, the patient reported diplopia in the upper and lower visual fields, image tilting, and ocular pain. No functional deficit of the right infraorbital nerve was detected.

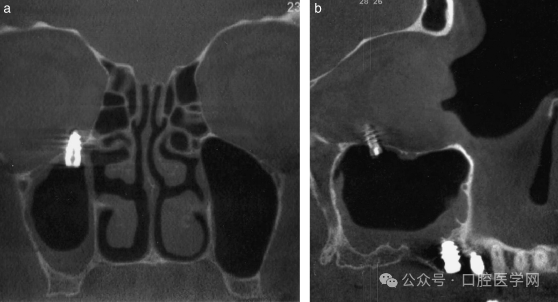

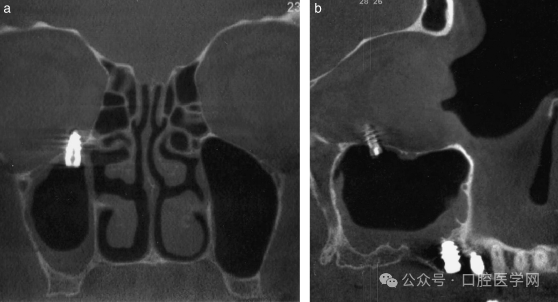

Panoramic X-ray and a maxillofacial CT scan revealed an implant located in the medial part of the right orbital floor, in contact with the inferior rectus muscle (Figure 1). This part of the orbital floor is typically robust and would not perforate unless subjected to external force.

In consultation with the patient, we decided to remove the implant endoscopically to address the diplopia and prevent complications such as orbital or maxillary sinus infection or obstruction.

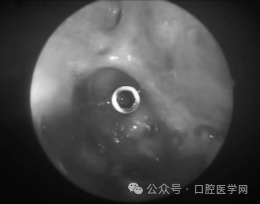

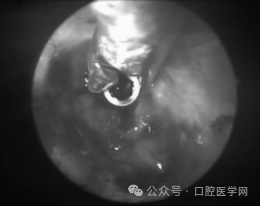

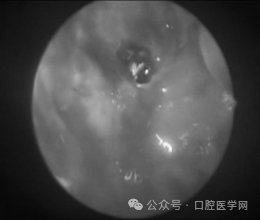

Under general anesthesia with endotracheal intubation, we used a 01 nasal endoscope to access the implant through the previously established oroantral fistula (Figure 2). The implant was located on the right orbital floor, 1-2 millimeters from the infraorbital canal (Figure 3).

Following the previously reported method (Felisati et al., 2007), we carefully removed the implant using Weil forceps (Figure 4). Minor bleeding from the orbital floor was observed (Figure 5).

We then closed the oroantral fistula with a Bichat fat pad (buccal fat pad) (Figure 6). The postoperative course was uneventful. Prophylactic antibiotic treatment began a day before surgery and continued for five days postoperatively, along with corticosteroid and analgesic therapy.

Postoperatively, the patient reported no further diplopia or sensory abnormalities. Ophthalmologic examinations and visual field tests at each stage indicated improved visual function post-surgery.

Discussion

Endoscopic techniques serve as an invaluable tool in the removal of foreign bodies, such as dental implants, from paranasal sinuses. They allow clear visualization of the surgical area with minimal patient trauma and faster recovery. Endoscopic surgery can reduce operative trauma and the risk of complications such as infraorbital nerve injury, which was particularly pertinent given the implant’s location in our patient.

A major risk for our patient was a retrobulbar hematoma. The dental implant was located in the retrobulbar position of the orbital floor: if retrobulbar vessels were damaged, it could lead to such a complication.

Various surgical approaches have been described in the literature for retrieving displaced implants, including oral approaches via the inferior meatus or the canine fossa (Caldwell-Luc approach). However, we preferred an endoscopic approach through the existing oroantral fistula, resorting to other methods if necessary.

After the removal of the displaced implant, the patient’s diplopia was entirely resolved. Fortunately, our patient did not experience traumatic rupture of the rectus muscle as previously reported in a study involving zygomatic implants.

Implant displacement during placement is understandable. It can be related to insufficient bone quality or quantity, lack of operator experience, untreated perforations, excessive implant tapping, or the application of too much force.

One might wonder how a non-zygomatic dental implant ended up in the orbital floor. Typically, displaced dental implants remain at the bottom of the maxillary sinus due to gravity. It is believed that the dental surgeon inadvertently pushed the displaced implant into the orbital floor using the suction device.

In conclusion, the endoscopic method is highly reliable and minimally invasive for the removal of foreign bodies from the paranasal sinuses. This case demonstrates its usefulness in managing a challenging case of dental implant migration into the orbital cavity. We advocate for the endoscopic approach as the first-line treatment for the removal of foreign bodies from the paranasal sinuses.

Leave a Reply