Root fracture (abbreviated as root split) refers to an incomplete or complete longitudinal split starting at any level of the root that does not involve the crown portion, typically buccolingual in direction, and usually occurring in teeth following root canal treatment. Diagnosing early root fractures, which include incomplete fractures and fractures where the fragments have not significantly displaced, can be challenging. Certain typical positive signs suggest the possibility of a root fracture, such as the presence of narrow and deep periodontal pockets, a sinus tract located near the crown, and periapical radiographs showing “L” or “J” shaped radiolucent patterns around the root. However, their accuracy and specificity are relatively poor, leading to the potential for misdiagnosis or missed diagnosis. The advent of cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT), which offers high resolution and three-dimensional imaging, seems to provide a good basis for diagnosing root fractures. However, studies have shown that artifacts from high-density root filling materials and limitations in CBCT resolution affect the definitive diagnosis of root fractures. Therefore, for teeth that have undergone root canal treatment, CBCT is not a reliable method for diagnosing root fractures. Early root fractures require flap exploration or minimally invasive extraction for confirmation under a microscope.

01. Root Fractures

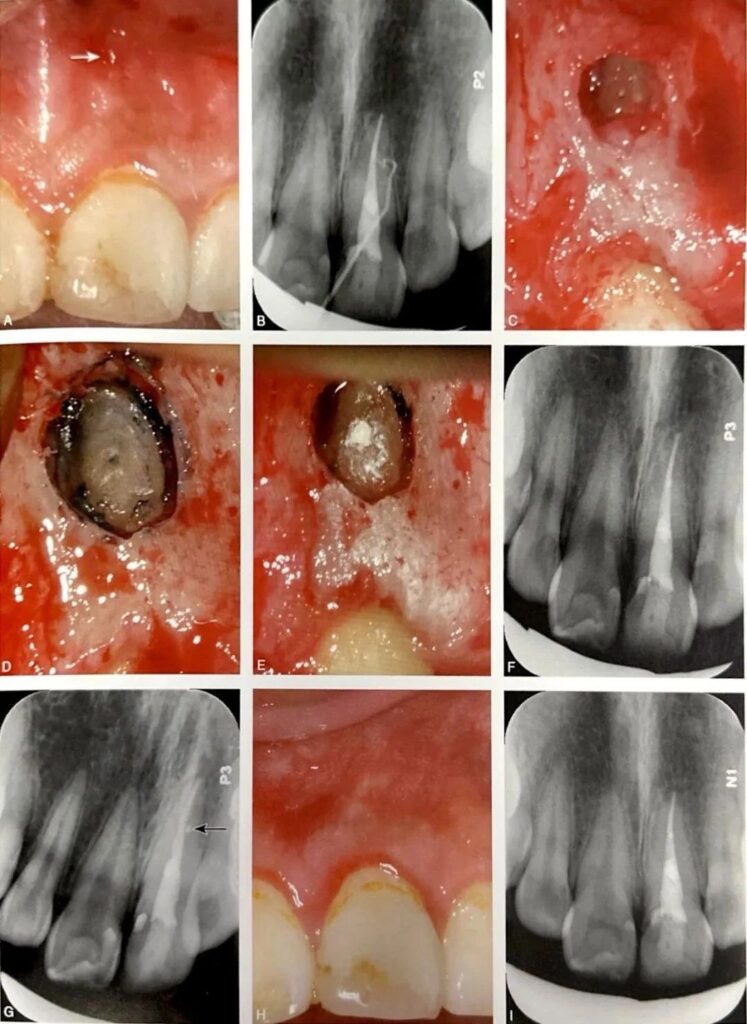

For root fracture lines that extend the entire length of the root, flap reflection or minimally invasive extraction followed by methylene blue staining and microscopic examination at high magnification can make detection relatively easy. Key diagnostic points include: the ability to stain, probe accessibility with a microscope, and destruction of the corresponding alveolar bone (Figures 1, 2). For incomplete root fractures, such as those limited to the apical segment in the crown-root direction or only located buccally or lingually in the horizontal direction, diagnosis is more difficult. Since root fractures often appear as irregular fractured surfaces extending through the root canal to the root surface, apical resection with staining can be performed to explore the root cutting surface and root surface. If the diagnosis remains uncertain and the root has sufficient length or is multi-rooted, root apex resection can continue until the suspected root fracture line completely disappears.

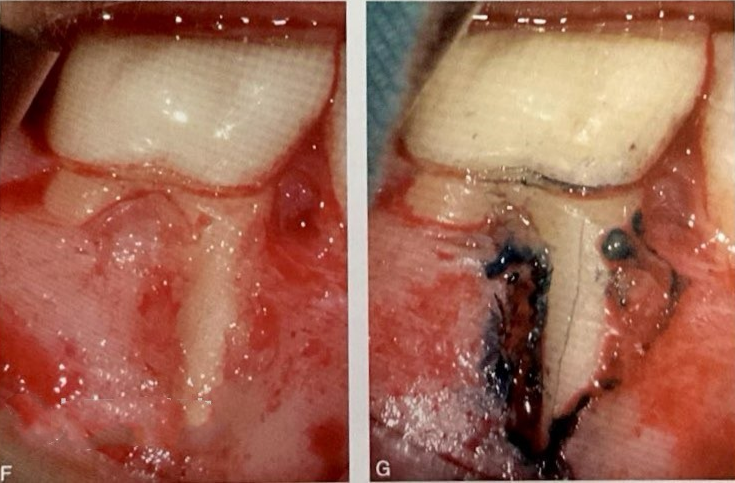

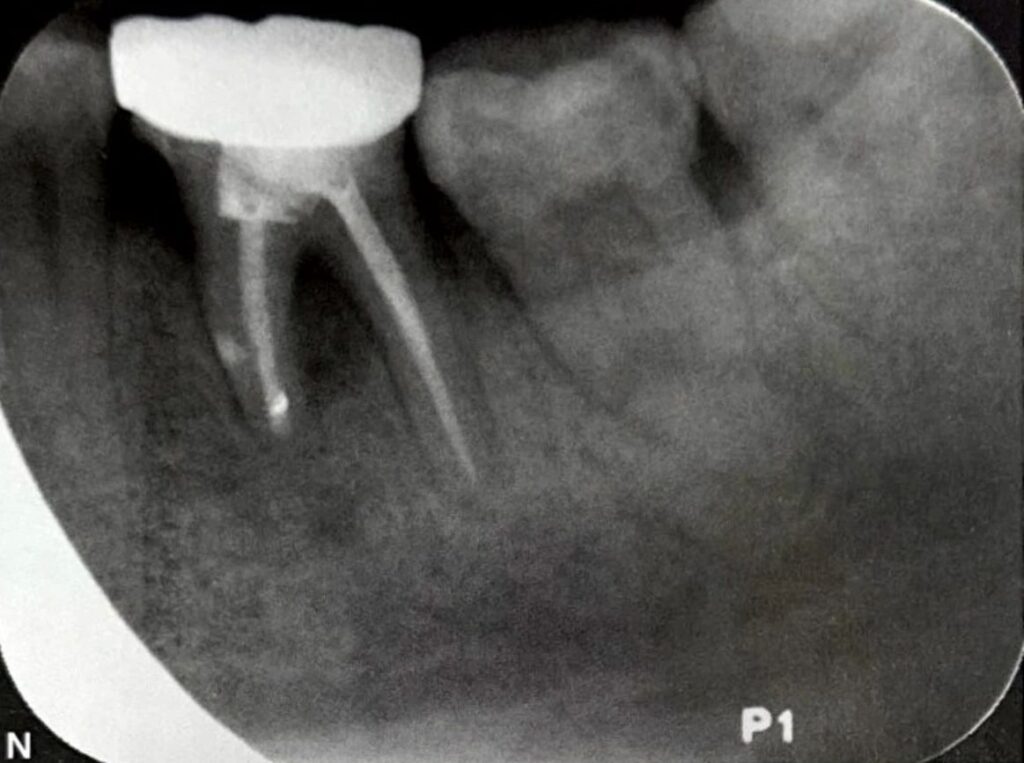

Figure 1. Mesial root fracture of the right mandibular first molar. A shows an intraoral image indicating a sinus tract in the buccal apical region of the right mandibular first molar; B shows a periapical radiograph with good root canal filling and periapical radiolucency; C is the CBCT sagittal view; D is the CBCT coronal view; E is the CBCT axial view showing apical and periapical bone destruction and buccal cortical plate defect; F shows the right mandibular first molar undergoing microscopic endodontic surgery with flap reflection and buccal cortical plate defect of the mesial root; G reveals a buccolingual root fracture line extending the entire length of the mesial root observed with staining.

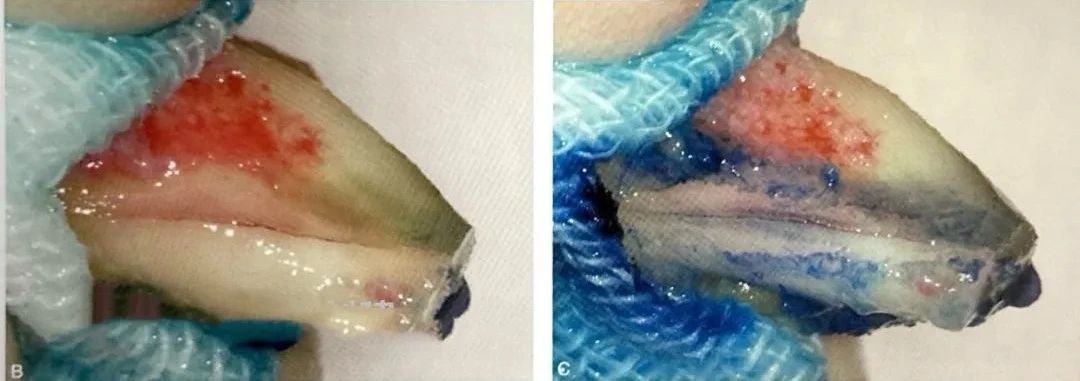

Figure 2. Root fracture of the left mandibular second molar. A shows a preoperative periapical radiograph with good root canal filling and periapical radiolucency; B shows the left mandibular second molar undergoing intentional replantation with minimally invasive extraction revealing a buccolingual root fracture line extending the entire length of the root; C confirms the root fracture with staining, and the procedure is terminated.

02. Lateral Root Canals

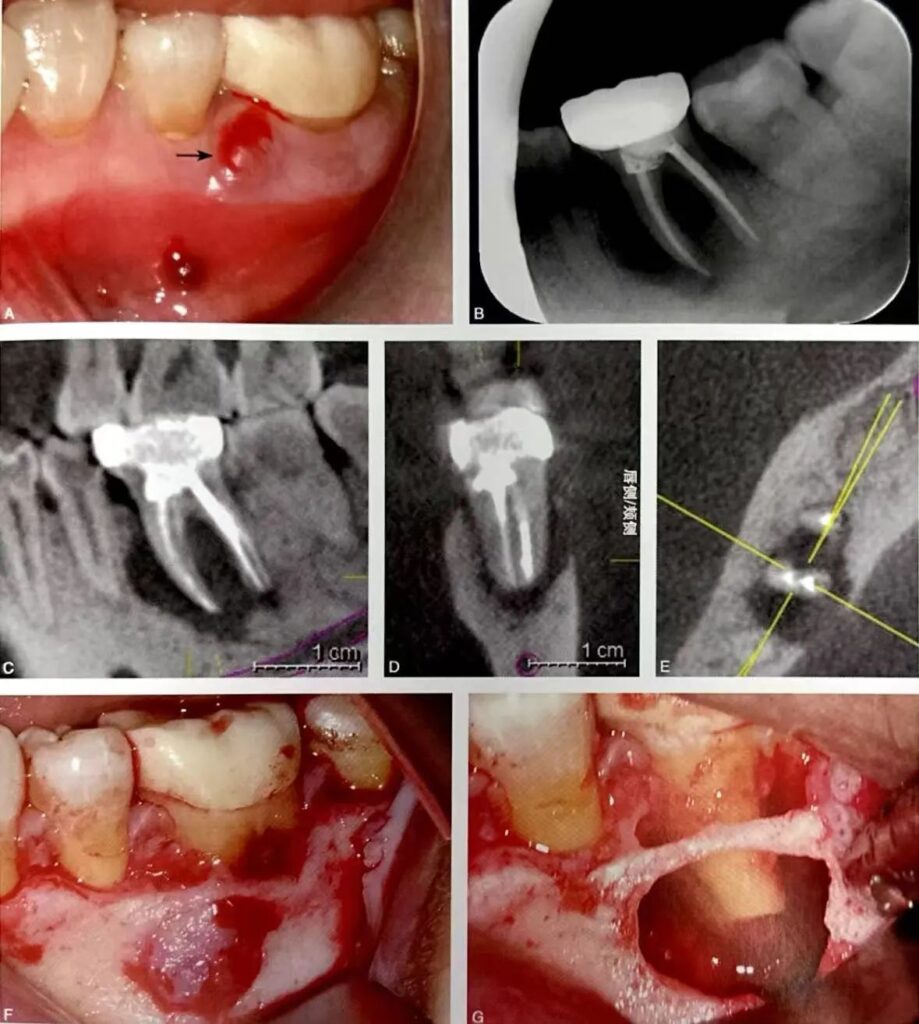

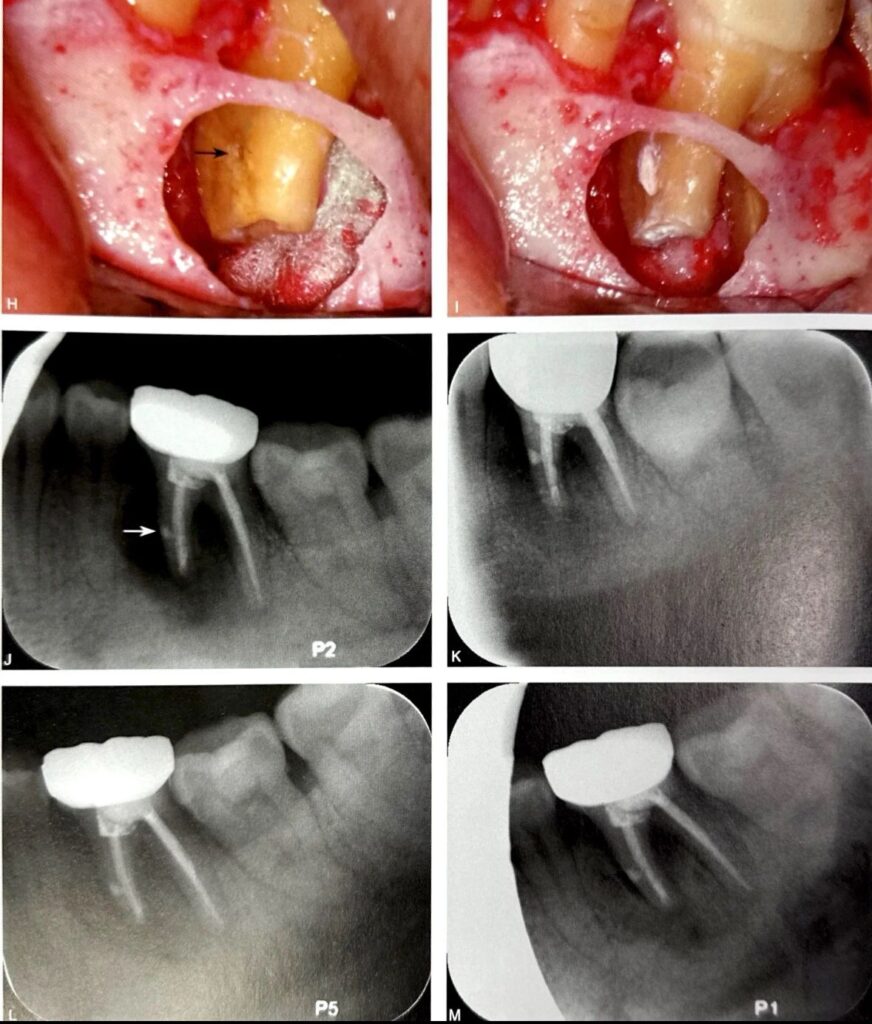

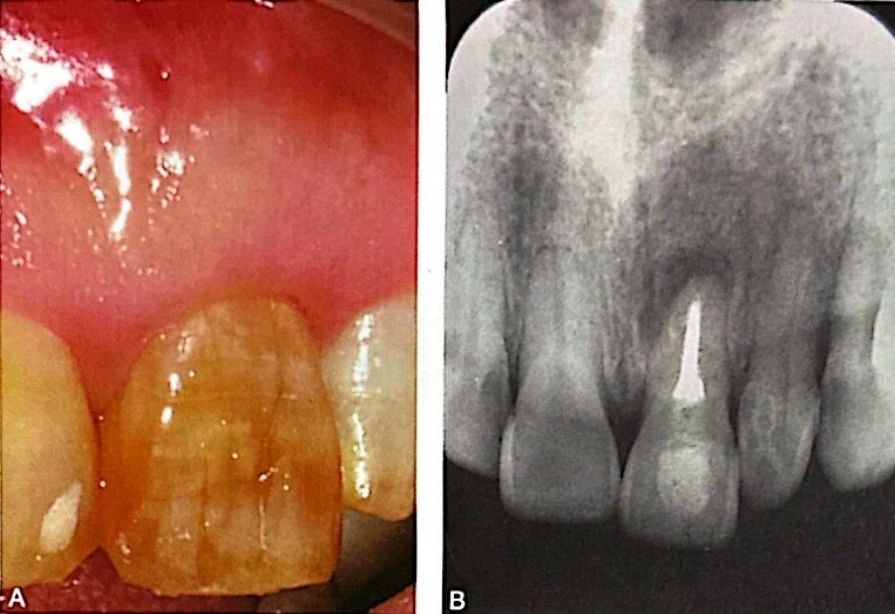

Potential causes of periradicular bone destruction include root fractures, lateral root canals, root bends, periradicular cysts, cemental tears, etc. When a lateral root canal is located in the middle portion of the root, infection can destroy the periradicular alveolar bone, forming radiographic features similar to root fractures, as shown in Figure 3. A shows an intraoral buccal view with a gingival sinus tract (arrow) near the gingival margin of the left mandibular first molar; B is a periapical radiograph showing good root canal filling with extensive periapical radiolucency involving the furcation area; C is the CBCT sagittal view; D is the CBCT coronal view; E is the CBCT axial view showing apical, periapical, and furcation bone destruction; F shows the left mandibular first molar undergoing microscopic endodontic surgery with flap reflection; G shows apical curettage and apicoectomy; H shows the mesial root without a fracture line, but a lateral canal is found in the middle mesiodistal section (arrow); I shows retrograde preparation and filling of the main root canal and lateral canal; J is the postoperative periapical radiograph showing the lateral canal (arrow); K-N show follow-up periapical radiographs at 2, 4, 7, and 24 months postoperatively with complete periapical and periradicular healing. Lateral canals typically have a diameter less than 100 micrometers, making preoperative radiographic diagnosis challenging. When lateral canals are larger, they may appear clearly on CBCT, as shown in Figure 4. A shows an intraoral buccal view with a sinus tract at the apex of the left maxillary central incisor; B is a periapical radiograph showing good root canal filling with periapical radiolucency; C is the CBCT sagittal view; D is the CBCT coronal view showing a lateral canal (indicated by an arrow); E is the CBCT axial view showing a lateral canal (indicated by an arrow); F shows staining after apical curettage revealing two lateral canals (indicated by arrows); G shows staining after apicoectomy revealing three lateral canals (indicated by arrows, with two arrows in the upper left indicating a microscope mirror image); H shows retrograde preparation of the root canal and lateral canals with fusion of two lateral canals near the root apex; I shows retrograde filling of the root canal and lateral canals (indicated by arrows); J is the postoperative periapical radiograph; K shows the follow-up periapical radiograph at 26 months postoperatively with complete periapical healing. Lateral canals are usually located in the apical region, with a few in the middle portion. Lateral canals in the apical and middle regions on the buccal or lingual side of the root are more easily diagnosed, as shown in Figure 5. A shows an intraoral buccal view with a sinus tract (arrow) in the middle portion of the root of the left maxillary central incisor; B shows a gutta-percha tracing periapical radiograph indicating the sinus tract originates from the middle distal portion of the root; C shows the left maxillary central incisor undergoing microscopic endodontic surgery with flap reflection revealing buccal middle root bone defect; D shows staining after curettage revealing a lateral canal; E shows retrograde preparation and filling of the lateral canal; F is the postoperative periapical radiograph; G shows an angled radiographic view of the filled lateral canal (arrow); H shows a 4-month follow-up intraoral image with normal gingival and alveolar mucosa and a normal periapical radiograph with normal periapical and periradicular bone; lateral canals located on the mesial or distal sides or lingual/palatal side of the middle root are prone to being missed, and should be observed using a microscope mirror reflection, or intentional replantation should be performed if necessary. When examining, lateral canals may exhibit different colors, with blue-black (unfilled) being the most common, and others being white (sealer filled) and yellow, red, blue, etc. (gutta-percha filled).

Figure 3. Lateral canal of the mesial root of the left mandibular first molar resembling a root fracture.

Figure 4. Preoperative CBCT discovery of a large lateral canal in the left maxillary central incisor.

Figure 5. Middle lateral canal of the root of the left maxillary central incisor.

03. Intercanal Isthmus

Another consideration in the differential diagnosis of tooth fractures is the intercanal isthmus. The mesial root of the mandibular first molar typically features an isthmus, which is also a common site for root fractures. In cases of chronic apical periodontitis in the mandibular first molar, if the intercanal isthmus is relatively wide, the periapical radiograph may exhibit features similar to a root fracture, requiring differential diagnosis. During root canal treatment, the following conditions may raise suspicion of a root fracture: the presence of a hidden crack line inside the canal observed under direct visualization through the pulp chamber with a microscope, abnormal working length measurements with an apex locator, or abnormalities in the sealing or filling images.

Leave a Reply