**Editor’s Note:** The fields of dental materials science, biomechanics, and denture fabrication are continuously evolving, leading to rapid advancements in oral restoration technologies through the introduction of new techniques and materials. However, due to geographical disparities and uneven economic development, there is a significant variance in the level of oral restoration technology across different regions. Continuing education for prosthodontists is an effective and crucial way to enhance national standards in oral restoration, and many practitioners are pursuing further training to upgrade their clinical skills and adapt to the evolving landscape. The quality of education for these prosthodontists directly impacts the improvement of oral restoration services, especially in primary care settings across the nation.

Peking University School of Stomatology, a leading institution for dental education and a training hub for high-level dental professionals in China, boasts substantial experience in the training and education of prosthodontists. What are the common clinical issues faced by prosthodontists? How are they resolved? This column, “Common Questions for Continuing Education of Prosthodontists”, will be launched in series to provide guidance on these issues. Here, Professor Jiang Ting from the Department of Prosthodontics at Peking University School of Stomatology addresses common questions regarding removable partial dentures.

Author Introduction:

Jiang Ting, a professor and chief physician at the Department of Prosthodontics, Peking University School of Stomatology, has engaged in education, research, and practice in oral restoration and physiology. She graduated in 1983 from the Fourth Military Medical University, Department of Stomatology, and earned her PhD in Dentistry from Tokyo Medical and Dental University in 1992. Since 1999, she has been with Peking University School of Stomatology and has served as a PhD supervisor since 2010. She was a senior visiting scholar at the University of Washington School of Dentistry from 2009-2010. Jiang has published over 50 articles in leading journals and edited or translated ten major works, including “Complete Occlusal Reconstruction” and “Practical Adhesive Restoration”, holding several national patents. She serves on the editorial boards of several journals, including the International Journal of Prosthodontics, and has led numerous national and Beijing municipal science funding projects, receiving third place in the Beijing Science and Technology Progress Award.

**Question:** What steps are involved in designing a removable partial denture?

**Answer:**

The design of removable partial dentures is complex due to the variety of tooth deficiencies and the intricate nature of remaining oral tissues. A clear approach is crucial for successful denture design. The design should prioritize support, retention, stability, aesthetics, and comfort, and these factors should guide the preparation of the mouth’s remaining tissues. Before starting this preparation, it’s essential to manage any remaining dental, periodontal, and alveolar ridge tissues by removing lesions and restoring health, or by providing restorations for abutments if fixed prosthesis is needed.

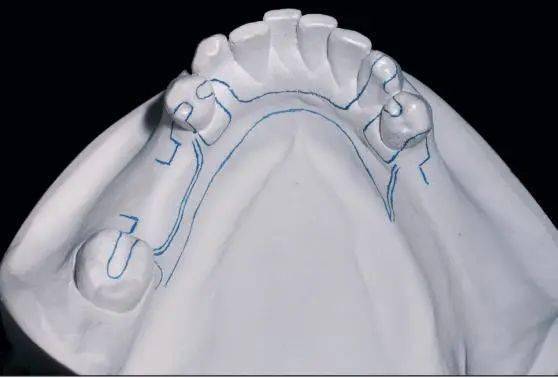

The design should be simple yet robust, focusing on the denture’s support and stability. It should minimize the use of excessive clasps and minor connectors. Before preparing abutment teeth in the mouth, it’s advisable to use study models to adjust the model’s angle with an articulator, sketching the path of least resistance for the denture placement and the high points on the abutment teeth to guide intraoral preparations. Here are the steps to follow in the mouth:

1. Design rest positions on remaining teeth: Place rests on abutment teeth near the edentulous area to achieve three- or four-point occlusal support across the dental arch, preventing pivoting. Options include molar rest, canine cingulum rest, or incisal rest; cingulum rests are often located on the maxillary canine and shaped in a transverse “V”, while incisal rests are designed on the incisal edges of the lower anterior teeth in a “U” shape. Prepare these rest seats by lowering the high points on the facial surfaces of the abutment teeth.

2. Design direct retainers (clasp assemblies): A single arch denture typically requires two to three clasps, each providing 400-800 grams of retention force. Too little force will not retain the denture adequately; too much can make it difficult to remove and risk damaging the abutment teeth. Additionally, remember the counter arms of the clasps. Different materials and flexibilities of clasps affect how deeply they can engage undercuts on abutment teeth; for example, wrought wire clasps and gold alloy clasps have greater flexibility, allowing deeper engagement depths of 0.75 mm and 0.50 mm, respectively, whereas cast circumferential and bar clasps enter at a depth of 0.25 mm. The tips of clasp arms should ideally point towards the edentulous area to maximize retention and minimize “pulling forces”. On a terminal abutment, consider designing a buccal-approaching circular clasp with an additional occlusal rest on the distal of the clasp to prevent breakage.

3. Design indirect retainers or minor connectors: These are placed away from direct retainers, such as occlusal, cingulum, or incisal rests, to stabilize the denture. If there are multiple edentulous areas (more than two), design guiding planes on abutment teeth adjacent to these areas that run parallel to the path of insertion. This allows the denture framework to form parallel guiding planes that fit snugly against the abutment teeth, limiting the denture’s movement away from the intended path and enhancing the indirect retention and bracing effect while reducing reliance on direct retainers.

4. Major connectors: These connect all direct and indirect retainers and the bases carrying the artificial teeth. In the maxilla, options include the palatal plate, anterior-posterior palatal straps, or palatal bars; in the mandible, consider a lingual bar or plate. For tooth-supported dentures, aim for a rod or strap design for major connectors: if the prosthesis includes distal extension cases, expand the base area accordingly. In the maxilla, the major connector might be a palatal plate or a windowed anteroposterior palatal strap; in the mandible with sufficient periodontal health and adequate depth of the floor of the mouth (greater than 7 mm), a lingual bar is suitable; otherwise, a lingual plate should be considered. Additionally, if the lower anterior teeth have severe periodontal disease or a poor prognosis and further extractions may be necessary, design a lingual plate or even a partial acrylic base to facilitate future additions and repairs to the denture.

5. Denture base extent: Design the extent of the denture base according to the number and location of the edentulous areas. For tooth-supported dentures, the base typically covers just the buccal, labial, and lingual aspects of the edentulous zones. For prostheses that include distal extension cases, the coverage extends beyond the edentulous areas: in the maxilla, around the maxillary tuberosities; in the mandible, covering two-thirds of the area posterior to the molars. Avoid excessive extension of the maxillary and mandibular buccal/labial denture bases to prevent interference with perioral muscles and soft tissues; at the frenum areas, allow ample clearance (a “U” shaped labial frenum and a “V” shaped buccal frenum), staying short of the deepest part of the vestibular sulcus by 2-3 mm. In the mandible, also clear the area at the distobuccal angle to accommodate the masseter muscle, forming an open “V” shaped notch, while in the maxilla, create a small “V” shaped notch at the pterygomaxillary ligament. The lingual side of the mandibular base should not be shorter than the level of the mandibular torus and mylohyoid ridge, with ample clearance at the lingual frenum.

6. Position and material of artificial teeth: When designing the position of artificial teeth, consider the location and occlusal relationship of the remaining teeth, ideally positioning the prosthetic teeth over the crests of the edentulous alveolar ridges to establish a normal interarch relationship. Depending on the patient’s age and functional demands, it might be appropriate to reduce the number. When opposing teeth are natural, due to the greater occlusal forces, opt for hard artificial teeth and a metal framework.

**Question:** How do different types of clasps affect the torque on abutment teeth?

**Answer:**

Wrought wire clasps offer greater flexibility, exerting less retention force and corresponding torque compared to cast clasps. Generally, the deeper a clasp engages under a high point of an abutment tooth, the thicker it is, and the greater the torque during insertion and removal. Regardless of clasp type, always include a counter structure on the opposite side of the retention arm’s force, such as a counter arm, denture base, rest, or minor connector, to minimize the torque on abutment teeth during denture insertion and removal.

**Question:** How to enhance retention of a removable partial denture when posterior teeth are missing?

**Answer:**

With missing posterior teeth, the primary means of denture retention shifts to the anterior remaining teeth. Due to the limited number and retention force of available direct retainers, it’s essential to maximize the indirect retention provided by the remaining teeth to ensure denture stability. Design proximal guiding plates that are parallel to each other on the sides of the remaining teeth adjacent to the edentulous areas. The major connector should be designed as a lingual plate or palatal plate, extending anteriorly to the cingulum of the canines to enhance indirect retention and support.

**Question:**How should a case be managed where there is severe periodontitis in the mandible, with few remaining teeth, non-mobile abutments, and one-third absorption of the alveolar bone to the apex of the root?

**Answer:**

Initial steps should involve periodontal treatment to maintain and prolong the life of the remaining teeth. Then, select abutment teeth that are relatively healthy, with adequate root length and periodontal ligament surface area (typically mandibular canines, ideally one on each side of the arch). After thorough endodontic treatment, crown the teeth at 1 mm above the gingival margin, apply a post and core plus a root cap to cover the roots of the abutments, and then affix a root attachment (such as a magnetic attachment or precision attachment) for the overdenture restoration.

Leave a Reply